More on Mentorship

Last year, I wrote about some of the aspirations which motivated my move from Mozilla Research to the CloudOps team. At the recent Mozilla All Hands in Whistler, I had the “how’s the new team going?” conversation with many old and new friends, and that repetition helped me reify some ideas about what I really meant by “I’d like better mentorship”.

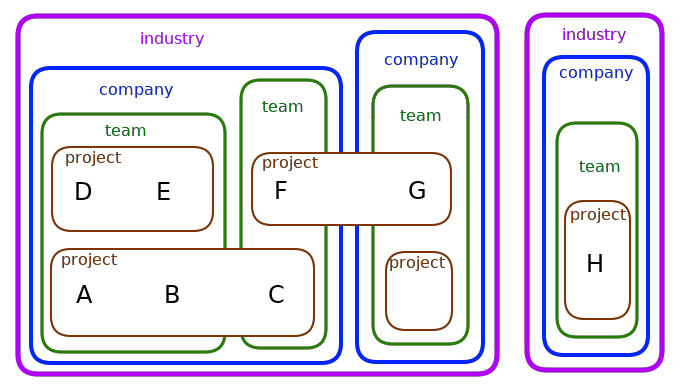

To generalize about how mentors’ careers affect what they can mentor me on, I’ve sketched up a quick figure in order to name some possible situations that people can be in relative to one another:

The first couple cases of mentorship are easy to describe, because I’ve experienced and thought about them for many years already:

Mentorship across industries

Mentors from outside my own industry are valuable for high level perspectives, and for advice on general life and human topics that aren’t specialized to a single field. Additionally, specialists in other industries often represent the consumers of my own industry’s products. Wise and thoughtful people who share little to none of my domain knowledge can provide constructive feedback on why my industry’s work gets particular reactions from the people it affects – just as someone who’s never read a particular book before is likely to catch more spelling errors than its own author, who’s been poring over the same manuscript for many hours a day for several years.

However, for more concrete problems within my particular career (“this program is running slower than expected”, or even “how should I describe that role on my resume?”), observers from outside of it can rarely offer a well tested recommendation of a path forward.

Mentorship across companies within an industry

Similarly, mentors from other companies within my own industry are my go-to source of insight on general trends and technologies. A colleague in a distant corner of my field can tell me about the frustrations they encountered when using a piece of technology that I’m considering, and I can use that advice to make better-informed choices in my daily work.

But advice on a particular company’s peculiarities rarely translates well across organizations. A certain frequency of reorganization might be perfectly ordinary at my company, but a re-org might indicate major problems at another. This type of education, while difficult to get from someone at a different company, is perfectly feasible to pick up from anyone on another team within one’s own organization.

Mentorship across teams within a company

When I switched roles, I had trial-and-errored my way into the observation that there’s a large class of problems with which mentors from different teams within the same company cannot effectively help. I’d tentatively call these “junior engineer problems”, as having overcome their general cases seems to correlate strongly to seniority. In my own expeience, honing the improvement of code-adjacent skills such as the intuition for what problems should be effectively solvable from the docs versus when and whom to ask for help, how deeply to explore a prospective course of action before committing to it, and when to write off an experiment as “effectively impossible”, are all questions whose answers one derives from experience and observing expert peers rather than from just asking them with words.

Mentorship across projects or specialties within a team

I had assumed that simply being on the same team as people capable of imparting that highly specialized variant of common sense would suffice to expose me to it. However, my first few projects on my new team have clearly shown, in both the positive and the negative cases, that working on the same project as an expert is far more useful to my own growth than simply chancing to be bureaucracied into the same group.

The negative case was my first pair of projects: The migration of 2 small, simple services from my team’s AWS infrastructure to GCP. Although I was on the same team as experts in this process, the particular projects were essentially mine alone, and it was up to me to determine how far to proceed on each problem by myself before escalating it to interrupt a busy senior engineer. My heuristics for that process weren’t great, and I knew that at the outset, but my bias toward asking for help later than was optimal slowed the process of improving my ability to draw that line – how can one enhance one’s discrimination between “too soon”, “just right”, and “too late” when all the data points one gathers are in the same one of those categories?

Mentorship within a project

Finally, however, I’m in the midst of a project that demonstrates a positive case for the type of mentorship I switched teams to seek. I’m in the case labeled A on the diagram up above – I’m working with a more-experienced teammate on a project which also includes close collaboration with members of another team within our organization. In examining why this is working so much better for me than my prior tasks, I’ve noticed some differences: First, I’m getting constant feedback on my own expectations for my work. This is no serious nor bureaucratic process, but simply a series of tiny interactions – expressions of surprise when I complete a task effectively, or recommendations to move on to a different approach when something seems to take too long. Similarly, code review from someone immersed in the same problem that I’m working on is indescribably more constructive than review from someone who’s less familiar with the nuances of whatever objective my code is trying to achieve.

Another reason that I suspect I’m improving more quickly than before in this particular task is the opportunity to observe my teammate modeling the skills that I’m learning in his interactions with our colleagues from another team (those in position C on that chart). There’s always a particular trick to asking a question in a way that elicits the category of answer one actually wanted, and watching this trick done frequently in circumstances where I’m up to date on all the nuances and details is a great way to learn.

The FOSS loophole

I suspect I may have been slower to notice these differences than I otherwise might have been, because the start of my career included a lot of fantastic, same-project mentorship from individuals on other teams, at other companies, and even in other industries. This is because my earliest work was on free and open source software and infrastructure. In FOSS, anyone who can pay with their time and computer usage buys access to a cross-company, often cross-industry web of professionals and can derive all the benefits of working directly with mentors on a single project. I was particularly fortunate to draw a wage from the OSU Open Source Lab while doing that work, because the opportunity cost of a hours spent on FOSS by a student who also needs to spend those hours on work is far from free.